If war has dehumanised, then art could have humanised or at least retrieved whatever was left. Yet this is denied through multiple negations when it comes to artistic production concerning Kashmir and Kashmiris, writes Compay Lizardi*

The problem with the contemporary art world (and there has to be at least one problem because otherwise, it can’t be much of an art world) is directly related with its absent, self-serving and self-interested distance masquerading as elitist comfort-zoning when it comes to the dispossessed and disenfranchised, and the subsequent engagement with them.

In what concerns subalterns and others, well, in quite reductionist terms those others are simply there for mere depiction, especially for the artist to produce the object of art where such others are portrayed from their particular location or environs and exhibited yet in an altogether different one, for multiple others to engage with. The prop-like presence of such subaltern subjects in certain artworks is problematic at various levels of critical inquiry because there is a general apprehension towards the aesthetic, ethical and political questions that emerge when marginalised communities, particularly the Kashmiris, come to the fore in depictions found in works of art, many times by distant or next to distant others.

I find it difficult to attend art-filled soirées, exhibition openings and other such events where the most fashionably dressed hang around to converse, while multiple depictions of subaltern others breathe on the walls, contrasting with the chatter abounding in elite institutional settings. To put it quite simply—how can you sip your wine and gobble your hors d’oeuvres while trying to have a pleasant conversation in the same space where a history of war, bloodshed, labour exploitation, class hegemony, casteist brutality, environmental degradation, human suffering, and struggle may be presented through the medium of art? Or is small talk taken as the normative means of communication in such settings? Well, well, it’s an exhibition, not a funeral, isn’t it?

Why should a spectator feel obliged to communicate one’s response to art verbally, particularly those works of art which stir something deep within each one of us in a subjective and unique manner?

How do curators establish the ground rules for an exhibition where serious matters and ideas concerning death, devastation, violence, genocide, and grief unravel the motifs that will be presented to a variety of viewers and spectators? Should a widely accepted model be developed or adopted to such scenarios of art and its exhibition? And more importantly, how to speak in the face of such images in such works huddled in a room full of art world personalities, when one wishes to engage with the art, rather than converse with those who can be easily contacted by other means? How to conceal emotion and response provoked by such? I seek silence in the gallery and the art space for such things, so it is easier to skip the opening night and visit an exhibition on some other day. But what if a new movement allows you to be masked with a t-shirt on that reads “I’m here just for the art, carry on” while attending such events, of course with a set protocol in place? Who would want to attend an exhibition seeking to engage with works that cover difficult subject matter, such that when the works work their way into your field of perception and evoke all sorts of ideas and emotions, you feel an obligation to cover up and not make eye contact with whoever is at the venue? Why should one upon one’s silent reaction and response being noticed quite visibly by an approximate other, require some sort of a verbalised enunciation, when they themselves ask the questions? Really? You want to discuss art in an art space full of people, when the artists, gallerists and members of the art community are present, and everyone has to greet everyone? An engaged spectator-critic must get out of the zone that art sometimes effectively puts us in due to the distractions of everyday conversation? Quite a contradiction, no? The depth of engagement that a work of art is capable of provoking versus the quotidian ritual of art event attendance. Why should a spectator feel obliged to communicate one’s response to art verbally, particularly those works of art which stir something deep within each one of us in a subjective and unique manner? This set of preoccupations are quite important to evaluate and consider,given the seriousness and dedication with which art is produced by a wide variety of artists, particularly about difficult topics or subjects,

When a work of art is absolutely magnanimous, powerful and great, talk becomes cheap. This is more noticeable in the social awkwardness of the art world. With its many artists, art enthusiasts, culture producers, gallerists, administrators, thinkers, curators and critics, who in one way or another are thinking on similar lines about all sorts of questions, or remain contrarily and willfully indifferent to certain questions and not others. Whichever the case, one’s personal response to art in an exhibition space should not necessarily be made to be put on display, as our faces register specific responses that are noticeable to others. In that, it is a mirroring of grief or a heightened understanding elicited through certain works that traverses generations and breaks all divisionary lines, rendering us human before ourselves and unto others. However, certain social settings and the possibility of a prevalent apathy are conducive to a type of surveillance by the surrounding certain others, who in one way or another will ask, sometimes mockingly, “what has gotten you all stirred up or so inspired?” Well, quite frankly my dear, I would rather just STFU, go home and write a 5000 word essay on it, instead of speaking in incomplete thoughts to someone who probably doesn’t care or care to know. In such scenarios, the most noticeable alienation is that of the artist, the one who stands quiet in some corner and has had to accept habituation of this particular ritual of the art event in its multiple variations.

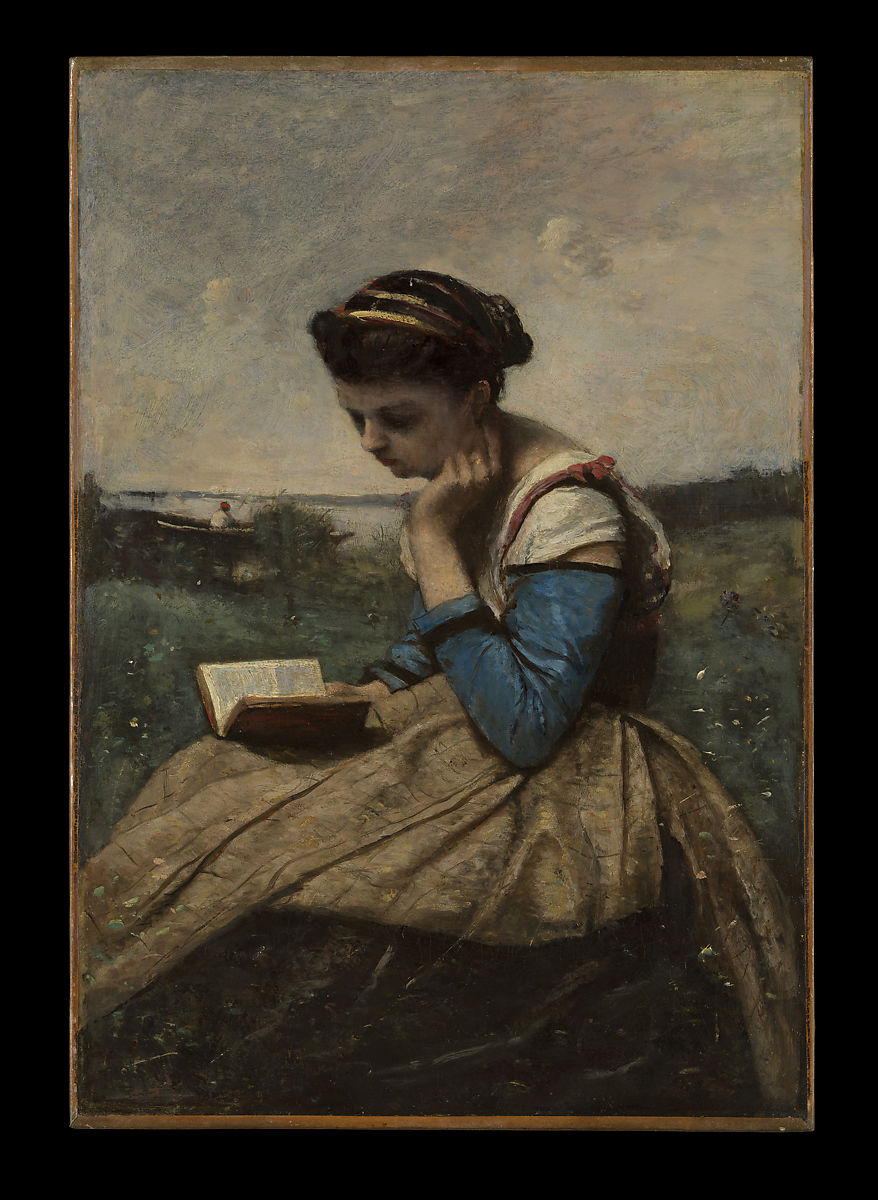

As such, would one be considered a rogue to posit the simple idea, actually, that one is indeed there just for the art and the impact it can facilitate to one’s understanding, perception, awareness, sensibility, and heightened engagement through a transformative illumination or a wandering off into the world that is encoded within the artwork? All these need not be the parameters that determine one’s engagement with a work of art, many times the silence suffices when the visual language of such works speaks for itself. Consider such an observation comparatively in terms of other places of congregation—you wouldn’t necessarily have to say anything to anyone at a concert, a film screening, a library, or even a grand museum. For matters of convenience, skipping over some big event that is announced to appear on an off day is far more logical. Similarly, consider the manner in which reading a novel in a public place, perhaps even a library, a jam-packed subway train, an airplane or a coffee shop, allows one to maintain a distance with those around, amplifying a set focus on the narration at hand.

Reading a novel in a public place, perhaps even a library, a jam-packed subway train, an airplane or a coffee shop, allows one to maintain a distance with those around, amplifying a set focus on the narration at hand. (Image: A Girl Reading, Camille Corot)

Cordial others intuitively see a book in hand as a symbol of “do not disturb” and know how to respect a needed distance. How then is one supposed to attend an exhibition where all sorts of profound emotions, complex epiphanies, and vast illuminations can be potentiated by the work of an artist, only to be disrupted by a crowd full of people on an opening night jovial as can be because they are seeing others in their community after a long while? Why not have the administrative bodies of art institutions alter their constitution of such events and revoke the particular articles that say you cannot show up in a numbered mask provided by the art space, unidentifiable to onlookers, and get to the task of engaging with the artworks while high-fiving the artist (if present) on the way out, all the while remaining quiet as a lake?

More people would be keen on going to see the works that artists so dedicatedly produce, less conscious of who they find there, from the #metoo accused,to this or that antagonist and instigator from some social circle, or that other one whose mere presence is a reminder of grief unaddressed and unquantifiable loss at love’s end. Imagine, in more practical terms—a gallery that asks you to register your name and number at their front desk, and offers you a numbered mask in case you want to avoid everyone in order to dedicate yourself to listening to what artworks have to say, to listen to the visual language craft out observations, to elevate you, to stir a storm within you, to soothe you, to illuminate you, or whatever it is that artworks do to spectators, because the responses are personal, subjective, and above all far too many, many times even for words. These are times where we go from social media chatter to art space chatter, such that critics, curators and art writers in one way or another are agents of freedom, understanding, support and empathy for artists whose vulnerability registers at multiple times in a world that seems stagnant and rigidly held in place by certain habituations and static customs that promote cynicism, bitterness, alienation and apathy.

In that context, consider that numbered mask system with a proper confidential registration system, for security purposes handled by the gallery staff. Imagine how it would open up the hermetic, restricted and closed-off art community and actually give more people access to a world of art that time and again struggles to be inclusive and fights at all odds to maintain inclusiveness as a symbolic foundation, both in terms of multiple representations, as well as institutional engagement. Wait, but are not galleries welcoming enough? Are art institutions not open for everyone to come to engage with works? One has one’s doubts, particularly if you look at the class-conscious and caste-conscious society beyond the gates of the art institutions in India, where an unspoken barrier does limit a lot of people’s access, apart from questions of social hierarchy and seniority that do not apply in many other parts of the world. For that, one can just read some Bourdieu about how internalisation at multiple layers works and social codification maintains unspoken barriers and boundaries between spaces, especially in South Asia.

Without deviating too much from this set of ideas, socialisation is indeed tedious and perhaps unnecessary on opening night, even though quite a few artists who visit such places on such occasions seem to possess an air of unspoken gloom over their heads. We are alone together in our sadness. There are possibilities for a non-alienated life.

Imagine the contrast in a specific instance—celebrating marginalised communities, because their marginalisation depicted and represented implies an attempt at inclusion, integration, awareness, and recognition. Multiple debates have long been covered in the academic realm in that respect, but for Indian art institutions to allow for the exhibition of Kashmir-related artworks becomes a matter of codified apprehension in the realm of the ethical and the political. While anything aesthetic pertinent to Kashmiri culture seems always welcome if one is to observe the Kashmir-related exhibitions within certain gallery circuits. This is perhaps due to the growing censorship and fear of vandalism that has established a long-standing tradition in the past, manifesting itself in more than recurrent instances.

Different institutions have different parameters for the prevalent thematic undertones that mark an exhibition, and yet I still wonder how one would open an exhibition centered around a massacre or the Bhopal disaster in a major Indian city. Again, different curatorial practices entail different strategies to set the tone and ambience of an exhibition space when such difficult imagery is presented through the medium of art. Sometimes clear instructions for visitors are listed on wall texts at the entrance of such exhibitions. However, one wouldn’t be surprised that in such gatherings on an opening night, eventually the attention shifts from engagement with the artworks and veers more towards a crowded exhibition space, full of people keen on conversing with one another after examining the works on display (quite simply because they haven’t seen each other for quite a while because everyone is always busy and we are all always working).

While no one can dictate or direct the multiple reactions and responses spectators will have, a certain distancing, or call it indifference, has had to have been normalized in such scenarios for some unfamiliar and oblivious spectators, in particular to the omissions that persist in portrayals of marginalised communities, or perhaps even their selective inclusion. An apathy for what is presented or perhaps even a sick voyeuristic engagement of people seeking to fill their inner void with something powerful that may perhaps move them or stir them in some way is another limited denunciation made by some. Take, for example, Ai Weiwei’s problematic staged photograph mimicking the pose of three-year-old Syrian toddler Aylan Kurdi as a poor attempt at some sort of a visceral solidarity. A graffiti-ed image of the departed child smiling is more effective on a street corner in stirring up the onlookers to never forget the larger tragedy from his concrete and heartbreaking demise. It is the one place where Ai Weiwei seems to get it all wrong, past all his iconic and groundbreaking artistic legacy of decades. Certain art world commentators seem to have quite a talent in boxing artistic productions in categories, like some who comment about cause-based art or art driven by political undercurrents, forgetting their relevance in Western art history.

The graffiti-ed image of Aylan Kurdi smiling is more effective on a street corner in stirring up the onlookers to never forget the larger tragedy from his concrete and heartbreaking demise (Image Courtesy: Deathscapes)

In what concerns Kashmir, the normalisation of state violence on Kashmiri subjects has led to its widespread acceptance in India over the last three decades. One would think that such acceptance has crept its way into the Indian art world, merely through its marginal or codified engagement with works by Kashmiri artists. Visual language matters. The work of Kashmiri artists appears in the Indian art world in fragments, in pieces, and not in some grand way dedicated to Kashmir’s existence under militarisation, conflict, and war. Inversely, the codified projections of Kashmir continue to occupy the social media, television channel and press spaces daily. Indian mainstream views persist, while the inclusive nature of the Indian art world stands to be questioned, time and again, so much so that young Kashmiri artists from the valley cannot ever think it possible to approach galleries with their works, unless some seemingly towering Kashmiri figure located in the Indian art-world lands in Srinagar to show them the way.

Again, class and caste apprehensions do apply within India, and certainly in the case of young Kashmiris who come with their own particular apprehensions and reservations, given an ever-expansive environment of conflict, militarisation and war. Within the high culture of artistic production and exhibition, as a symbol of civilisational progression and cultural innovation that is constantly in-flux, divisionary lines along various parameters do still apply. Beyond that, there are the usual city-based gatekeepers who will determine which young artist goes through and which one does not, sometimes hindering the exponential growth a young Kashmiri artist can have, provided the proper institutional access or the means to imagine that such access can happen through independent and self-motivated engagement with the world of art. Yet everyone does what they can, amirite, since traditionally-speaking, there is a hierarchy in place that does not always care to identify talent, encourage and empower it, cultivate it, while mere seniority counts to guard the gates of access in a few cases. Nonetheless, independent art spaces have been silently emerging within Kashmir over the last few years, and they require participation and engagement from the world beyond the Himalayas, which will hopefully happen eventually, depending on what circumstances unfold as major policy shifts completely restructure and shift perceptions and forecasts of what a future Kashmir will look like, with or without its already wounded Kashmiri ethos intact or in utter shambles.

Independent art spaces have been silently emerging within Kashmir over the last few years, and they require participation and engagement from the world beyond the Himalayas. (Image: Rollie Mukherjee)

Meanwhile, the oddity of entering a gallery space, where in certain cases a shift of attention from art to people and their everyday conversations, does posit a basic question, depending on the depictions of subaltern subjects in art that is on display in a gallery full of people—how does one approach such disparity and contrast, or even such abject negation and disrespect towards the subjects of such depictions that elicit such “moving” responses from an otherwise indifferent or oblivious spectatorship (to not simply call it an Indian and an international one)? Does experiential knowledge or a biographical bond to the subject matter depicted in art alter the way we see it in social settings, particularly in crowded gallery spaces?

More concretely, how would a retired army officer see a pellet-ridden depiction of a body presented in an artwork somewhere in Defence Colony? Only that particular and thus far hypothetical retired army officer can answer that. Can such images ever be allowed to exist beyond the stereotyped and orientalised projection that mainstream media maintains over such bodies and their criminalisation under the nation-statist discourse that has permeated into all aspects of civilian life? Can art be allowed to humanise those dehumanised by utter marginalisation in the arena of conflict, beyond the politicised (mis)representations that are prevalent in other mediums? It is this disparity and contrast that will not be comfortable to address for quite a few institutional players in the Indian art world, more so at this time. In fact, the question cannot even be raised by certain key players, and you know it. The resulting impossibility again validates a few potential observations—the toothless tiger status of the art world and a deafening silence, that from a Kashmiri perspective unveil complicity along with general apathy for the marginalised and the silenced of Kashmir. Since in certain instances, the “art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable” quote by Mexican scholar-activist César A. Cruz cannot apply, one should think then, that writing and thinking about art in that context should at least attempt to disrupt solidified notions and taken-for-granted withdrawals to remedy unquestioned invisibilisations.

As for images of the marginalised and traces of their existence manifest in exhibitions, there is no set standardised protocol for such presentations, and the maturity of the visitors is the measure by which a sense of respect is established. Anything beyond that depends on curatorial decisions as to how a space is to be organised and how an audience is forecasted to interact with the set space.

In that, consider a show by a particular artist exhibiting works about difficult themes, like the variety of ways in which Kashmiri lives are altered and destroyed within the particular and larger context of conflict, presented to an oblivious, uninformed or even a disinterested audience. At all times, the artist exhibiting such works is at the center of consolidating contradictions and contrasts, as the connecting subject between two worlds left to deal with the resounding disparity that marks that peculiar and dissonant distance between those who are depicted in the works and those who get to observe them and their condition through the frame of the artist’s portrayal. All this, in internationally recognized institutional settings, particularly in the remote possibility of art emerging from or inspired by Kashmir and its struggle for justice and peace, beyond the overreach of competing nation-states that dictate the reality of seven to eight million Kashmiris already historically encapsulated in the Himalayas.

In the case of Kashmir, the distance from the subject of depiction, to those who get to engage with it through art is severely tainted (Image: Ehtisham Azhar for Kochi Biennale )

And no, there are no specific alternatives to getting out of this conundrum of unavoidable disparities between subject matter and unfamiliar audiences, and yes, there are instances where such art escapes the fortressed altars of galleries and museums and enters the sites of depiction themselves. Public art, street performances, graffiti, interventions of all sorts do redeem the self-fortressing that alienates the art world’s many spectators, such that one thinks that the art world does not exist at the centers of the world’s culture-power nexus but rather at the most recondite margins of everyday life. Yet artists decidedly seem to find ways to disrupt the self-serving alienation that institutional settings are ossified by—that peculiar dissonant and withdrawn observatorium of the lives of multiple others in some faraway land, on some contested territory, in some distant ghetto right around the corner, and down the street.

In the case of Kashmir, the distance from the subject of depiction, to those who get to engage with it through art is severely tainted by what is specified in this article. Yet art-making inherently alters and adapts its object-subject through ideas, approaches, methods, and modalities. Commemoration, memorialisation, or simple cognisance do offer redemption from the fortresses of distance and wilful ignorance, and in the human domain potentialise avenues of empathy, understanding, alternative experience and perspective. The other is not the one depicted but the one whose gaze otherises, because multiple inversions are possible in the spaces that artworks offer for engagement, i.e. artworks stare right back with their peculiar gaze, and that may scare certain spectators whose stereotyped engagement with Kashmir stands challenged by Kashmiri life, its demise and its continued struggle for perseverance against all the odds and impositions. As usual, it all depends on the one who is looking.

A gallery space where a piled-up mound of pellets removed by hand from hundreds of Kashmiri bodies are put on display would not be a pleasant sight (for those familiar with what pellets actually look like), because each pellet is a reminder of the colossal violence that cannot be questioned in the Indian imaginary, much less be allowed to enter into such sites to disrupt viewers into empathising with the absent, invisible and tortured bodies that not too long were embossed with such markers of human atrocity, authored through a particular militarised legal framework. Such works will in clear and present terms, bluntly and without any consideration, be labeled as propaganda in the Indian art world while the artist will have to face libel from all directions apart from serious scrutiny. Meanwhile, the same cannot be said of the international art scene.

Art-making to an extent is about the impossible made possible through the artifice of the artist. All such possibilities reside in approximations and engagements from multiple entities who regulate and mediate the spaces where art can be accessed, especially in terms of bringing awareness about the lives of those who have been invisibilised, ignored, sidelined, othered beyond the othering they are already subjected to in the amphitheater of war and conflict.

How does a one-hour-flight geographical proximity create such remoteness and unfamiliarity? For all intended purposes, such contradictions are set on purpose when it comes to engagement with Kashmir via the medium of art. Needless to say, the impossibility of the art exhibition resides in a fear that can unite or at least lend itself to a compassionate understanding. Unfortunately, even that is too much to expect in the specific cases of those who get to decide what and what not to exhibit and show.

Under such circumstances, Kashmir and its representation historically and in present terms threatens all pretense, putting at risk the exposition of a hypocrisy, one that cannot be allowed to manifest as visible and clearly distinguishable. In this, there is a clear distinction between hypocrisy and contradiction. And beyond that resides the impossibility or rejection of a language and vocabulary of resistance, a cry from the Himalayas disrupting the institutional order that in turn orders Kashmiris to be institutionalised in a particular fashion, according to certain coordinates of relatability that are steeped in prejudice, characterisation, dehumanisation and imposed silence. It is engagement on our terms, not yours, you do not exist, except for how we wish for you to exist. The mainstream media does this quite well, while the art world risks either following its own designs (with its struggling tenets of inclusiveness) or becomes completely mute because the stakes are too high. It is no wonder that Kashmiri critics and artists themselves are found debating the elements of an orientalist and orientalising gaze drenched in exoticas galore, especially when it comes to engagement from certain centers where art is produced and exhibited.

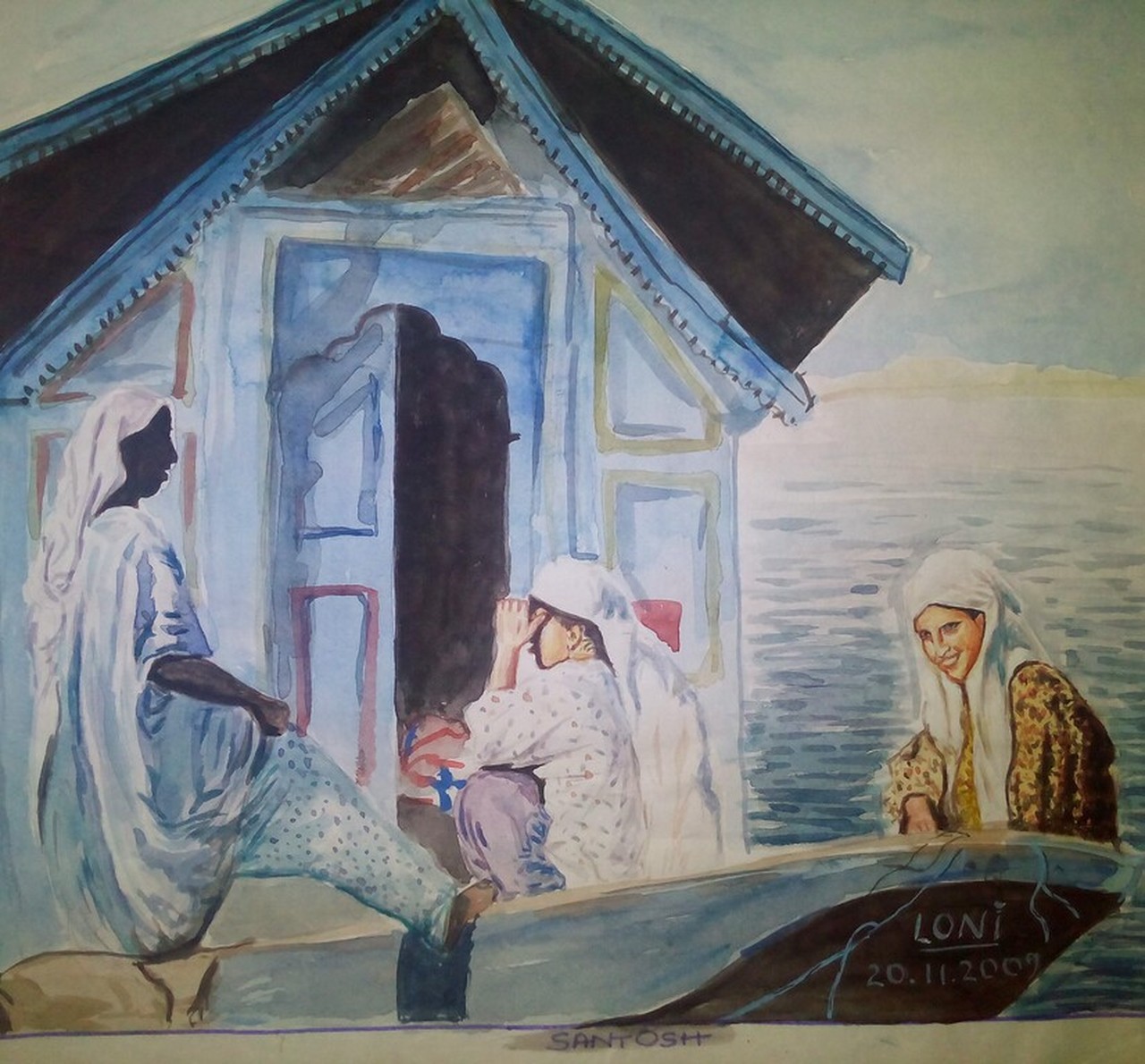

The restrictions that apply ensure, that even depictions which are traditionally reserved for Bollywood’s portrayal of Kashmir also remain enforced in specific instances of such Indian art-making where Kashmir and its subject figure somewhere. In such particular depictions, a normative gaze tends to exoticise the Kashmiri landscape and the Kashmiri subjects that are contained within it, or at best results in borrowing elements of Kashmiri culture to be presented in an altered form, to serve the Indian audience a comfortable, tailored and acceptable visualisation. The primary malaise is the detachment of the aesthetic and post-aesthetic from the ethical and political undercurrents that holistically characterise art-making in its engagement with specific subject matter. In such generalised observations as concrete denunciations, contemporary Indian art risks favouring the aesthetic and post-aesthetic while de-prioritising the ethical and political aspects that can be retrieved from the engagement with certain artworks, particularly in the combative terrain that maintains a concrete position on Kashmir. Such a recurrent disproportion manifest in fragments here and there only reveals the de-personalisation of art. Since art that omits ethical and political questions also omits certain subjects, making it rather impersonal and removed, and that too in a South Asian society where persona, person-hood, individuality and its towering cults mark the terrain of the human figure. In the arena of such towering projections of the human figure, the marginalised remain ever absent and invisible, more so now than ever before.

A normative gaze tends to exoticise the Kashmiri landscape and the Kashmiri subjects that are contained within it, or at best results in borrowing elements of Kashmiri culture to be presented in an altered form, to serve the Indian audience a comfortable, tailored and acceptable visualisation. (Image: Santosh Loni)

As a consequence, the impossibility of relating to, connecting with, and comprehending multiple negated, stereotyped and invisibilised others matches the neglect that power maintains over Kashmir and its people. Must art be political? some have asked, while conversely others have interrogated with is this art or artivism? when it comes to Kashmiri expressions finding their way into artistic depictions at the center of the art world. The young Kashmiri artists in formation tend to ask themselves time and again,”how do you transcend conflict in your art as a Kashmiri artist who is born into it, as the entombed subject of conflict?”. To be left for dead while quite alive is a lingering feeling that besieges far too many Kashmiris in what they call the forgotten conflict, concealed from the world and enclosed within the Himalayas. The latest policy developments are an absolute affirmation of that lingering feeling, amplified further by almost two months of silence as entombment.

And in that particular entombment, it is rather odd to study art history and the disruption in depicting or the crisis of representation (depicting what, pls specify or consider revising the sentence) that World War I incited with the advent of Dadaism (when artists felt they could no longer portray the world as it had become in a state of world war and its many nationalisms). The rupture from conventions, tradition, coherence and logic brought about in many ways as a response to what Europe had become during World War I still indicated a sense of care and concern, since it was better to unleash madness and externalise chaos through the artistic medium than to subject oneself to the logic that had brought the world into conflict. Thus the impossibility of representation, as the entire group of artists of that Dada generation envision, had a redeeming quality, remarkably expressed as a manifestation of protest, since the horrors of the world and its World War realities elicited a cultural response where artists chose no longer to be depicters of the world around them, rather receding into wilful nonsense, chaos, incoherence and illogic.

If war has dehumanised, well then art could have humanised or at least retrieved whatever was left. Yet this is denied through multiple negations when it comes to artistic production concerning Kashmir and Kashmiris in certain institutional settings. And that in itself marks quite a sick habituation as a simple question to be considered in particular ways—how do you mute and invisibilise a particular visual language, and restrict the expansion of its artistic vocabulary? Well, quite simply ignore it or pretend it doesn’t exist. And that too in an environment curtailed by censorship. Hence, the neglect is two-fold. The nexus of culture-power-state-institution remains intact while Kashmiri artists find alternative art worlds from which to develop and unfold their art practices at such a present and historically slow and struggling pace that unannounced cartographic alterations redirect human life almost overnight. One has to ask, how will grand policy shifts alter contemporary Kashmiri art-making?

The other limitation then is found in yet another question that has quite often been a topic of debate in the Kashmiri art and literary community: must artists come pre-branded as depictors and reproducers of a conflict-based thematic? A personification of people in various mediums is one of the greatest horizontally and vertically aligned practices of colonialism, because traditionally personification in literature is reserved for those who are not human, from talking animals, plants, fish, etc. As such, dehumanising and then personifying human subjects is synonymous to characterising them, and particularly in this, artistic intervention could have redeemed this denial of basic humanity in its own enclosed space and limited ambit.

In situations of conflict, in the terrain of cultural production, the condition of subalternity is marked by voicelessness, that doesn’t simply manifest by some odd magic of certain subjects being marginalised, but rather a voicelessness that is determinedly produced through multiple ways of silencing, which in aggregate lead to the dehumanisation that allows for a characterisation by means of personification. Such structuring allows for essentialised binaries such as The Evil Kashmiri Muslim and The Heroic Soldier, The stone-pelter Zombie Drug Addict Adolescent and The Clean Cut Bureaucrat’s Son. If conflict reduces and essentialises subjects to a dehumanised state, art-making and artistic expression could have humanised such subjects, particularly in their condition of victims. In what concerns the militarised conflict entrapping Kashmir, considering the traditional creative Indian lens, even the language of compassion, empathy and understanding are vastly ‘light-years distant’ to the otherwise ‘one-hour-flight’ geographical proximity that Kashmir is known for in relation to India.

In situations of conflict, in the terrain of cultural production, the condition of subalternity is marked by voicelessness, that doesn’t simply manifest by some odd magic of certain subjects being marginalised, but rather a voicelessness that is determinedly produced through multiple ways of silencing. (Image: Crafted In Kashmir)

Quite a cell to be enclosed in, when being Kashmiri entails being unlike any other, being unique, particularly in the domain of culture, within the arts and humanities and any discipline of knowledge where Kashmiri life figures as distinct and non-replaceable (in a voluminous tradition of scholarship, writing, literature and art-making that spans generations and centuries, traverses divisions between communities and forming a composite understanding of culture, with common and shared references manifest in the practice of everyday life, in multiple languages). To consider a simple example, an evaluation of Kashmiri literary history reveals a genealogy of progression that presents a holistic reading of Kashmiris as highly complex peoples with highly detailed and developed distinctions that converge and intersect on cultural, historical, ethnic and anthropological planes. However, all such profundity and sophistication of cultural development, that serve as markers of identity past any particular religious divide, have been overlooked in the mass media, or are strategically touched upon to comment on their loss, given the political upheaval of the 90s.

It is in the sphere of art, investigation, intellectual and academic inquiry where such complexities can be found and retrieved to present Kashmiris with the depth that is logically observable through centuries of converging and being in one place. However, the redundant patterns of Indian mass media’s representation of Kashmir and its peoples do not allow for such deeper approximations to flourish, many times negating a majority, in favour of a minority, while other minorities are completely ignored in mass-mediatised discourses and narratives of portrayal subservient to certain political views. As such, there is a Kashmir that the world beyond the mountains does not get to see, nor experience, nor comprehend, with an art-world oblivious to the human and cultural worth of Kashmiri peoples or what they can teach, communicate or bring into the arena of cultural cognisance. And within this framework, one finds a process of problematic trans-culturation (a merging or convergence of cultures in often uneven ways) in sync with a process of acculturation (an assimilation of one culture into another culture) to bring about a neo-culturation (the resulting creation of new cultural phenomena) that is at the centre of conflict, war, inequity, erasure of indigenous cultural practices, particularly ones that maintained a composite order and harmony.

Now, trans-culturation and acculturation can have both negative and positive connotations depending on the place of power and its performance on the everyday lives of people. From what they are served on the television, to what they read in the press, and what stylised or politically framed information they are exposed to on the internet, trans-culturation and acculturation in the context of conflict can bring about a neo-culturation that in reductionist terms is nothing more than an affirmation of Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilisations” argument to further exacerbate multiple hostilities, aggressions and sheer and pure hatred based on essentialised binaries of “us versus them.” It is precisely here where art-making in its multiple manifestations along with cultural production could have interjected to present human complexity, to further a deeper understanding, to expose various characterisations and personifications, and to create spaces of commonality where peoples of all sorts connect through expressions of music, literature, art-making, filmmaking and storytelling that are common to all cultures.

Yet in the prism of geopolitical conflict and war, all such forms are regulated, negated, omitted and outright ignored by the process of invisibilisation, and the voicelessness that Kashmiris from multiple walks of life denounce routinely through whichever avenue of expression is available to them. Meanwhile, the unresolved histories of dueling nation states mark every aspect of everyday life in Kashmir, beyond which Kashmiris struggle to maintain their sense of cultural specificity, communicable only internally, and not translatable to the outside world in the theatre of globalisation, transnationalism, cross-cultural dialogue and multi-culturalism that has historically seen Kashmir as a place of convergence.

To provide a simple example, the names of things in the Kashmiri language vary in terms of geographic location once one ventures from one part of Kashmir to another. One would, for example, have to investigate the exact point at which the word telewoad becomes czochiwoar when travelling from Anantnag to Srinagar, when both words refer to a bagel-like piece of bread garnished with poppy seeds (yes, poppy seeds, or even sesame seeds). All such things are more specifically explainable by Kashmiris in far more elaborate terms, especially considering phonetic variations and different pronunciations and accents, all revolving around a piece of bread that is commonly served along with cups of nunchai. And yet all a Kashmiri can perhaps think of is how to strategically make it to the baker, or find a baker, with a shop open for the morning and afternoon bread, all depending on the situation on-ground, with the blackout progressing towards the 40th day at the time of writing this sentence. That is what conflict, and militarised living does, it forces one to be pragmatic, to focus on the immediate, to set one’s mind and one’s eyes on what is immediately right ahead, in the struggle for everyday life and its sustenance, while basic inquiry, a larger set of questions, a more abstract mode of thinking, is lost in such imposed concentration. All the vastness of Kashmiri culture along with its distinctive and unique existence is lost to the daily mediatised belligerent uproar that inversely maintains Kashmiris under a sentence of perpetual silencing, while television anchors shout over participants and participants shout over one another. If Medusa’s snakes had hands, the number of facepalms would still fall short at this state of things, especially at the present juncture. What gets displayed, put on exhibit, and amplified, and what is concealed, invisibilised and put on mute mediates the terms of invisibilisation, silencing and overlooking the greater depth of a peoples neglected and maintained at the margins of their own cultural introspection.

After all, invisibilisation has to do with silencing and overlooking, and the maintenance of these two over a lengthy period of time until memories of distinctiveness can no longer can be sustained after a certain number of generations. For those unfamiliar, and quite expectedly so, Kashmir has sustained its diversity in terms of geo-cultural location, being the point of convergence between Central Asia and South Asia, with access to the Silk Route, on the highway to Europe through Russia, surrounded by India, Pakistan and China. Over centuries, the type of development that had facilitated a Kashmiri ethos, with its particular Kashmiri language and its multiple distinctions, has been overlooked and undermined since the advent of a borrowed idea of modernisation that through its most vicious manifestations presents itself in terms of hostile South Asian postcolonial nation building yet to be finalised or “settled.” In this regard of nation states still in the process of resolving their identity crises through territorial expansion, that Kashmiri uniqueness and particularity in the human domain stands negated, invisibilised or simply constrained in one way or another, reduced to themes of violence, war, conflict, exile, loss, and grief.

Under such circumstances, beyond the figure of the Kashmiri artist as a mere communicator of conflict and its many polarisations, a resistance maintains that artists define themselves through their work, and thus cannot be defined or confined by others, and that a shift must occur where contemporary art by such Kashmiri artists reflects on everyday aspects of Kashmiri life and Kashmiri culture, well beyond mere depictions of conflict and war (which in either case will manifest in artworks one way or another, because the absent always makes its presence felt in the process of critical inquiry and engagement). No one likes to be typecast, even though the Bollywood industry thrives on it with actors who make careers out of archetypal roles. However, one is bound to investigate how the traditional Bollywood gaze that portrays Kashmir finds its way into the Indian art world’s depiction of Kashmir. Artworks that are too blunt and literal in their presentation may quite easily fall into this categorisation or at least become subject to its scrutiny.

And for that simple reason, amongst many others, multiple inversions are required, because after all, for the world at large beyond Bollywoodesque approximations, Kashmir has to be more than a Led Zeppelin song or a posh wool sweater or some metaphor for Paradise Lost or Heaven on Earth or a serene holiday setting gone wrong. Whatever the case, the world at large has not bothered to tune in to Kashmir or much less cared to as the article suggests. For that blunt ignorance to be replaced with knowledge, Kashmiri artists exist to teach life through their artistic articulations, while death, desolation, and killings abound and institutions of art education are non-existent or restricted to a few in a society where individual initiatives have struggled to create alternative spaces, unknown to the outside world.

Kashmir has to be more than a Led Zeppelin song or a posh wool sweater or some metaphor for Paradise Lost or Heaven on Earth or a serene holiday setting gone wrong (Image: Vintage Kashmiri Pashmina Ad)

In the context of art-making, there is a vast difference between absence and invisibilisation. In that, many times absence materialising through an agential power, while invisibilisation in the case of Kashmir and its peoples, is typically enforced, while concurrently some other projection is routinely presented in the mediums of mass communication. In that, the art world had a clear power in presenting a deeper understanding and view of Kashmir and its people, but that would have entailed risking the act of humanising that art is known for, and that too in direct opposition to the dehumanisation that all else beyond such an arts and humanities bound art world constantly struggles to perpetuate. Unfortunately, not too many takers want to join that art party, and if that is the case, well then marginalised communities elsewhere stand to interrogate the art world of its sin of omission* or in the least, its questionable politics of depiction.

Finally, in an Indian art world taken to a satirical extreme, one day there will be an exhibition on the #metoo movement in India and none of the victims will be there as spectators to find some sort of cathartic solace, justice, or a sense of healing and solidarity. Similarly, there will be an exhibition on Dalits without any Dalits in the audience. Labouring bodies, rural subjects, transgender others, the aboriginal community of this and that place, the African diaspora without anyone else there, these and those remarkably unique peoples from this and that place depicted on gallery walls, and the spectators, indifferent, oblivious, and self-involved, utterly self-involved spectators in certain cases, especially on exhibition opening nights, will carry on with the usual meet and greet. Questions of representation and participation cannot simply be symbolic. As such, the proposed masked spectator figure, discretely concerned with a dialogue with artworks, stands as a type of positively invisibilised figure, unidentifiable by face and name, that would redeem the other type of invisibilisation of marginalised and silenced subjects that manifests consistently, with fragmented disruptions every now and then when artists take on initiatives of engagement with marginalised communities through their respective art practices.

In all such cases of contradiction and contrast, the pressure of many disparities converges on the figure of the particular artist, the one who actually goes beyond the aesthetic and post-aesthetic presentation into the realm of the political and ethical to retrieve the personal (of the subject depicted). Such an artist is at times interrogated about the subjects of their representation and sometimes questioned in obtuse ways about whether they are orientalising the subject of such depictions for distant eyes to look upon. It depends, because at the center of orientalism is the question of power manifest through the gaze of the powerful. Nonetheless, there are (even remarkable non-Kashmiri) artists who invert that power through their artistic production, such that the muted and silenced speak loud and clear through images, text, and media. And the interrogators unsettled by the artworks that stare right back at their spectator-status are the ones who will obtusely formulate such questions about orientalisation and exoticisation without a deeper engagement, and much less a nuanced attempt at understanding. In such ways, if an aesthetic (l’art pour l’art) and a post-aesthetic approach disengages from the personal, the ethical and political approaches to art-making that drive right into questions of personhood, identity, individuality, subjectivity, all notions that are otherwise denied or abjectly negated in humanising a dehumanised subject of marginality, war and conflict.

Conversations in the Kashmiri art community, whether in the valley or the diaspora, tend to question whether artists should investigate ways to transcend conflict-centric art-making, simply because conflict instantiates its own subtle presence even in such potentially elusive art-making, in one way or another, for as long as it persists. Irredeemably, absence makes its presence felt, as do the absent, against any given sin of omission.

*Sin of Omission,a short story by Ana María Matute, the most widely known woman writer of post-war Spain who was 10-years-old when the Spanish Civil War erupted, and lived under Franco’s regime for 36 years. Her story Sin of Omission is about a thirteen-year-old orphan adopted by a negligent distant uncle, who sends him off to work as a slave on a faraway farm of the family’s estate. As five years pass, the boy upon realising his sorry state, in direct opposition to the progress of his soon-to-be-lawyer distant cousin, abruptly murders his uncle in a frenzy and is taken to prison while the villagers around him denounce him for being an ingrate, who did not appreciate the work and life opportunity that his uncle had blessed him with.

Ana Maria Matute

The story unveils a metaphor for dehumanisation in the face of forced child labor, slavery, and exploitation. All three of these are omitted from narrative description as the orphan’s harsh life of menial labor remains remote and invisible in the plot sequence, while contrarily towards the end of the story, a bout of unforeseeable jealousy manifests in his abrupt act of violence. In Matute’s story, the sin of omission is minutely observable in the careless, indifferent and negligent uncle who sends off his nephew to work on the family farm in exchange for taking him in and providing him with food and a place to sleep (to earn his keep). Again, the focal point of the narration in descriptive terms is on the family estate and the figure of the uncle, while the invisibilised Lope, taken in at age thirteen and sent off to work, reappears five years later as an eighteen-year-old worn-out young man delivered from serfdom to criminality. A Marxist interpretation of the story is far too elementary and perhaps far too boring and superficial.

*Compay Lizardi is the nom de plume of an art critic inspired by the literary writings of José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi, the famous Mexican journalist-turned-novelist, and writer of the first Latin American novel, who from time to time wrote under the pen name of The Mexican Thinker.