An art residency in Bapugaon, Maharastra witnessed joyful camaraderie as Warli artists welcomed their UK counterparts, writes E. Dawson Varughesea

At the recently concluded Indian Ceramics Triennale(ICT) in Jaipur, there was an installation which was part of Heart: Beat*, an exchange residency between the UK and India. Scholar E.Dawson Varughese talks to Joanne Ayre, artist and Studio Programme Manager of the British Ceramics Biennial based in Stoke-in-Trent, UK about the project, what she has learnt about Warli art, cultures and practice, and how she came to create her own Warli-inspired work.

Read the excerpts below.

EDV: Please tell us about your work in the UK, Joanne.

JA: I was born and now work in a city in the UK synonymous with ceramic manufacture,Stoke-on-Trent. I have been working with clay since I was a teenager and after studying and living in Cardiff and London, I returned to Stoke-on-Trent to live and work in 2015. My practice is concerned with people, place and process, how clay as a material can be used to communicate with others, through heritage and culture. I am interested in why, how, when and where things are made as much as what. My work within the British Ceramics Biennial studio has been driven by an interest in what happens when people are given the opportunity to experiment with clay, what relationships form and how the landscape of a city might change.

EDV: How did you come to be part of Heart:Beat Joanne?

JA: During2016, when the Heart:Beat project began for me, I was also part of a residency with the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery and Air Space Gallery, UK investigating the work of women within the ceramics industry in Stoke-on-Trent,UK. This research was carried out through ‘making’ alongside ‘talking whilst making’.I wanted to connect this research with my approach to the residency in Bapugaon, particularly as the tradition of Warli painting appeared to have a gendered history. I was also interested in the aim of the Heart:Beat project in providing impetus for the creation of a Kendra, a centre that celebrates the heritage of the area, but also, finds a way of ensuring that the craft is viable for the future, which is the way that my work with the British Ceramics Biennial in Stoke-on-Trent is focused.

EDV: Please describe how you first came to experience Warli art.

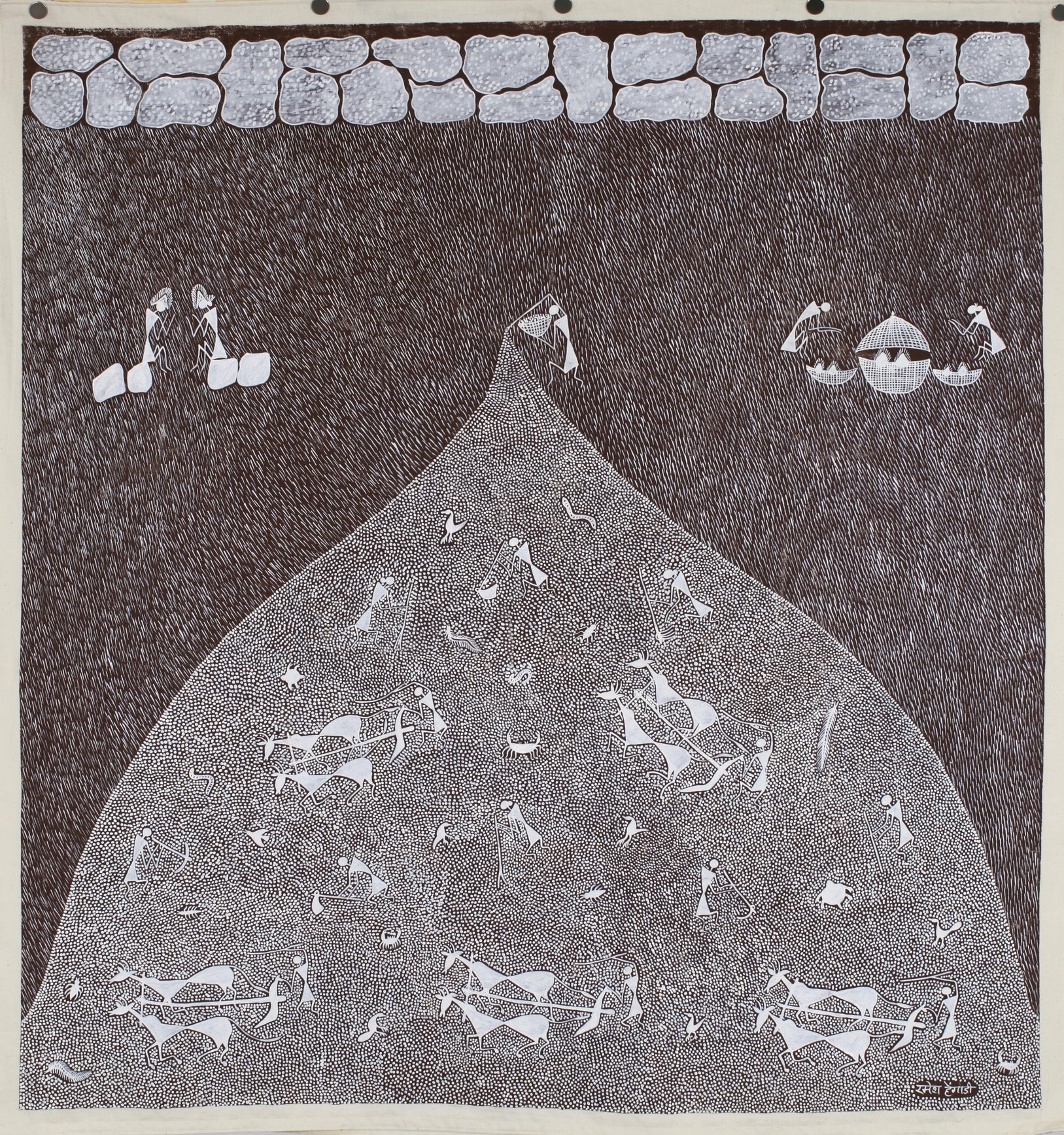

JA: My first encounter with Warli art was at the V&A Museum of Childhood exhibition The Tales We Tell in London which featured works by Jivya Some Mashe and Ramesh Hengadi. I met with Ramesh whilst he was on residency at the museum and he subsequently made a visit to Stoke-on-Trent so that we could experiment in the studio along with Professor Steve Dixon from Manchester School of Art, one of the other exchange artists. I also supported Ramesh in the education work he was involved in at a London primary school; this gave me time to look, think and ask questions, about the artwork, the context, the Warli tradition and relatedly, the contemporary approach.

EDV: How was the experience of working with the Warli artists in India in terms of the collective endeavour and communal living?

JA: The whirlwind two-week residency was a time to research, make work of our own, then help to bring into reality the first imaginings of a Kendra at Ramesh Hengadi’s home.There was something special about being part of a collective effort, with our energies all focused on creating a collaborative showcase for the work of the local Warli artists.It was a unique personal experience, but with moments of familiarity, echoing the common endeavour alive at home in Stoke-on-Trent. One of the most memorable moments for me was working alongside some of the women artists in the village.A stand-out moment was the day that work began on the wedding chowk painting.

The women who painted the chowk, worked from Sangita’s porch, the house adjoining Ramesh’s. There the two women painted together,rested, chatted, and sang. Whilst the initial patterns were mapped out onto the panel, the women filled the air with their song. The song had a drone like quality to it, with a continuous overlaying of sounds. Voices feeding in and fading out, it is said that the sound directs the painting.

EDV: What did you make while you were there?

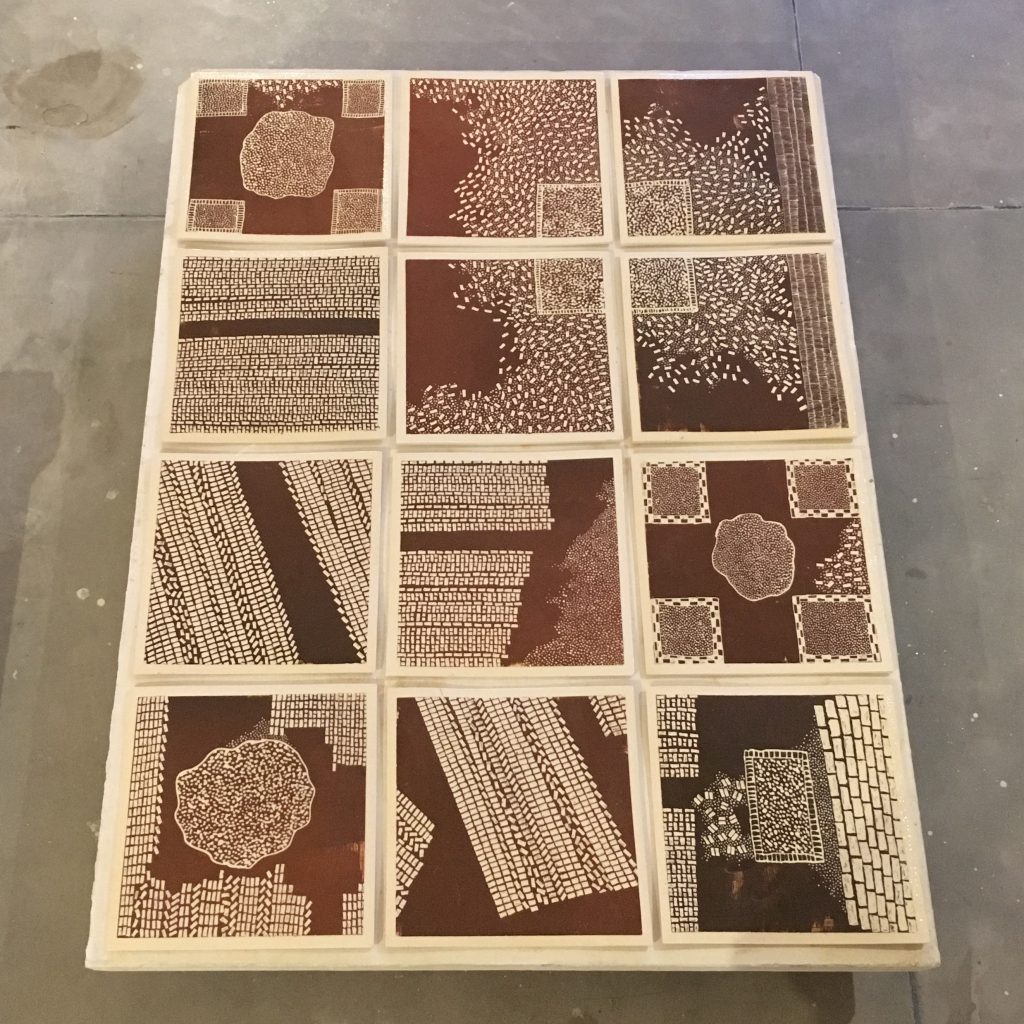

JA: Despite the briefness of our stay, I felt a connection with Ramesh’s family and friends. I was warmly welcomed into their lives and the source of much amusement, particularly for the children, as I tried to carry things on my head, thresh or pound the rice. The pieces I developed whilst there referenced the domestic activities connected to rice. I worked alongside Rasika, Ramesh’s wife and a painter in her own right, and many other members of the team joined us, to add grains of rice to one particular piece. The canvases I worked on express and reflect on the rituals of rice, the role it plays both in daily life and the making of art in Bapugaon; it is both subject and material. I worked with cow dung and rice paste to create these works, taking motifs of rice,in different forms, from the paintings I had seen.

Returning to work in the studio in Stoke-on-Trent with the more familiar material of clay, here too, the material became the subject. The marks on the tiles are suggestions that move between Bapugaon and Stoke-on-Trent; a patterning of slip that flutters between image and form, recording shadows and glimpses,recollections of one place overlaid with another.

EDV: What were the most challenging and also rewarding aspects of the Bapugaon residency for you?

JA: Stepping outside of Ramesh’s home, the experience of visiting a brickyard had a profound effect on all of the artists from the UK, where pairs of husband and wife labour for long hours to mix clay, form bricks, stack them, dry them, then stack again to fire in huge structures.There is nothing to romanticise here, it is hard work in harsh conditions.However, the field of raw bricks, laid like carpets and stacked like screens, is a sight to behold. The vast physical record of the skill and deftness of the brick makers is there in the landscape, and thrown into sharper focus when you realise that there are people working in between these rows, shuttling to and fro, or wading chest high in the clay pit, mixing the slurry for the next day’s making. This experience resonated deeply with the artists on the exchange and it became one of the sustaining thematic connections throughout the artists’ work made since.

EDV: What has happened since the artists’ exchange?

JA: Since the artists’ exchange the project has touredas an exhibition to Ahmedabed, and to Nottinghamshire, Stoke-on-Trent andRochdale in the UK, each time changing and developing with the introduction ofnew works that have grown out of the exchange. The most recent development has taken place in Jaipur with a residency and exhibition as part of the inaugural Indian Ceramics Triennale, thanks to the support of the British Council. Ramesh, Rasika and myself, supported by Heart:Beat creative director, Barney Hare-Duke, had two weeks in Jaipur at both the Indian Institute of Craft and Design and the Jawahar Kala Kendra, to devise, design and fabricate new works,both painting and ceramics. The installation became a live project space, and includes raw materials, tiles, bricks, ceramic, moulds, working processes,objects and paintings, with film and sound. It includes works created off- site by the other, UK-based, Heart:Beat, project artists; Stephen Dixon –ceramicist; Jasleen Kaur – artist; Johnny Magee – film maker; Jason Singh –musician sound artist. The works together constitute a body of work Made Out Of Place and gives impetus to the idea of developing local making,learning and exhibition spaces in both Bapugaon and Stoke-on-Trent where cultural production will continue to take place and be developed.

EDV: Did the Indian Ceramics Triennale offer any new directions for the artists involved?

JA: Yes,it provided us with a chance to further not only the tangible outcomes of a collaborative and conversational way of making, but the plans for developments of the partnership between us as artists and a contextual link between the two locations of Bapugaon and Stoke-on-Trent. We were able to widen our discussions with other practitioners to include more general ways of working with notions of tradition and rooted practice, across hierarchies and categories of artisans, craftspeople and artist, as well as notions of value and individual autonomy. It also acted as a springboard to launch a reciprocal residency for an artist, put forward by the Indian Contemporary Clay Foundation, to join the British Ceramics Biennial in 2019.

EDV: What are the next steps for this partnership?

JA: We hope to be putting on an exhibition of new works in Delhi with Gallery Threshold next year. After that, we will be refocusing on the next stages of the Warli Kendra in Bapugaon. We are reacting to the reception that the project has had within the wider context of India and the UK and building upon the wider relationships that are needed to ensure that the vision has a viable future for those who are able to not only sustain the art form, but to imbue it with expression and individual voice.

*The Heart:Beat project was started in 2006.The Warli Project which was initiated by UK-based A FINE LINE: Cultural Practice as part of an international artists’ exchange between India and UK. The principal funding for Heart:Beat came from Arts Council England the British Council as part of the Reimagine India campaign programme in 2017.

E.Dawson Varughese is an independent scholar who works in the UK and India see her work at www.seeingnewindia.com and www.beyondthepostcolonial.com.

Joanne Ayre is an artist who works with clay and is also the Studio Programme Manager for the British Ceramics Biennial based in Stoke-on-Trent, UK. www.britishceramicsbiennial.com