As questions about India’s free Press continue to make their presence felt, a dive into Indian history reminds us of the daunting battle fought on papers with ink and opinions, writes Suyash Verma

By the end of the 18th century, Printing Press was a widely practised profession in Europe. Gradually the art of printing reports at its face value evolved into a distinctive faculty of Journalism. Journalism brought to the Press what Prometheus brought to humans, the blessing of knowledge. The fervour of honest reporting spread like wildfire across the world and brought a revolution by springing the ideas of independence into animation that shocked colonisers into silence.

Journalistic consciousness in the Indian subcontinent arrived with its colonial burden. European newspapers failed to represent and defend the interest of Indians and thus circulated amongst a handful of its European readers. The standards were eventually raised by the vernacular press which, unlike their European compeers, spoke of shortcomings in the administration and openly criticised the Government. Nevertheless, European Press exercised considerable power and privileges, owing to their racial superiority. As the years went by, the distinction between the two opposing ideological houses grew more extensive, which earned them new monikers- Anglo Indian Press and Indian Press.

Newsrooms holding strong opinions had to walk out of the publishing business for speaking out the truth. Contrary to all expectations, the first to fall under the heavy hands of censorship was the Anglo Indian Press. In the beginning, it featured, to the annoyance of the colonial government, affairs and scandals of British officials. James Augustus Hicky, who started a weekly newspaper in 1780, was infamous amongst the British for his off-colour writings which spared not even the Governor-General, let alone the lower officials. The chitchat of Hasting’s administration were passed by members of the Governor’s Council, who might have disliked him for personal reasons. After learning that his private life was being tossed around in the newspaper, Hasting denied Hicky’s Bengal Gazette the government’s postal services for its circulation, on the grounds of disturbing the peace in the English colony. Slanders, lawsuits, and inability to pay fines eventually led Hicky behind bars.

The Government often targeted Anglo Indian journalists with liberal opinion for seditious reporting. A well-known editor, James Silk Buckingham, landed in ideological clashes with the government for which he was deported. Reputed newspapers like India Herald and Weekly Madras Gazette also came under the vigorous inspection of the government for inflammatory reports.

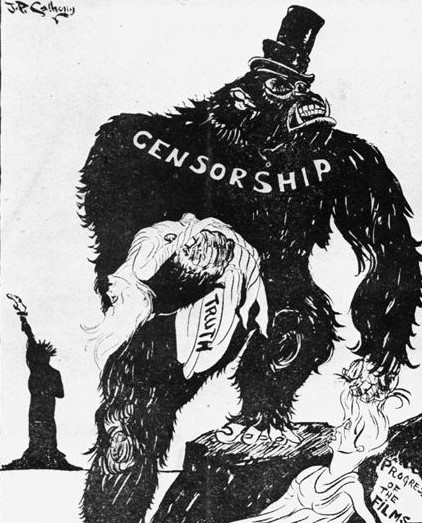

Anti-Censorship Cartoon (Film Mercury 1926)

Liberal Anglo Indian and vernacular publications’ reported of revolution and freedom struggles across the globe. British were well aware of the threats that knowledge exhibited. It was no secret that knowledge was a medium of enlightenment and Press a mechanism to disseminate it. An abled English administrator, Sir Thomas Munroe once expressed his prophetic concerns about free Press in his minute dated 13th of April, 1822-

“….But we cannot with any reason expect this silent and tranquil renovation; for, owing to the unnatural situation in which India will be placed under a foreign government with a free press and a native army, the spirit of independence will spring up in this army long before it is ever thought of among the people.”

Not to his surprise, unrestricted Press did serve as the fodder and fuel during the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 when many Vernacular papers in manuscripts cleverly and provocatively ran news against the Government. W.B. Bayley, a conservative member of Governor’s Council while deciding on whether to muzzle the Press or not, also reflected a general understanding of colonial opinion about free Press by saying –

“Stability of British dominions depends upon cheerful obedience and subordination of the officers and upon the opinion entertained by superstitious and unenlightened native population…..The liberty of Press is thus not consistent with the character of our institution in this country.”

The Government passed the first Press ordinance in March 1823, which directed all unregistered Publication Houses in India to obtain a licence from the Governor-General. This intentional deterrence drew acute flak from people who thought of free Press as a tool for education and social reformation. The social reformer behind the fight against the practice of Sati and child marriage, Raja Ram Mohan Roy took up the mantle of giving the ordinance a tough fight. After losing a legal battle to revoke the ordinance in Indian court, he took it to England by appealing the King in council, albeit to no effect. This still was a small setback, and a bigger challenge was yet to come.

Driven to it (Dalrymple)

The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 that had spread across northern India shook the mercantile government to the core. The memories of bloodshed between the natives and European communities left a permanent dent on the future of free Indian Press. Thus, the real tug of war between the Indian Press and Government began after the events of 1857. The priorities of Anglo Indian Press shifted after the Empress took over the fretted mercantile government which had failed to manage the rebellion of native soldiers. Although a few chose to maintain the editorial integrity, most of the jingoistic Anglo Indian Press together with the Government, came down hard upon the Indian Press and its readers. Lord Canning, after implementing the Act V of 1857, infamously known as The Gagging Act, effectively gagged the voice of Indian publishers. Under it, the Government made the scrutiny of draft reports mandatory before printing. Nonconformity was made punishable under the law. Daily and weekly newspapers like Durbin, Sultan- Ul – Akhbar and Sudhavarshan were indicted for inciting rebellion.

Another censorship law, the Vernacular Press Act of 1878 was an attempt to silence leading vernacular papers like Anand Bazar Patrika which often ran against the tide by infusing the spirit of nationalism in its writings. In an attempt to avoid intentional restraints brought on the regional language papers, many turned into full-fledged English papers overnight. A great deal of readership got impacted due to linguistic alteration, and many regional language editors lost their medium of expression as a result.

The restraints on Indian Press ranged from libels to financial sanctions. The government demanded security deposits ranging from five to ten thousand rupees from Indian media houses. The penalty went as high as one lakh. More than 450 newspapers went out of service due to such high hand actions.

The first half of the 21st century was filled with humanitarian crisis as a consequence of wars and droughts. The government,often in an attempt to avoid inconvenient views, tried to conceal the reports of such events to fall under the scrutiny of Indian Press. Nevertheless, the news of devastation across Bengal during the year 1943 was brought to every doorstep by Vernacular Press and liberal Anglo Indian Press. The newspapers were prohibited from using the word “famine”. But, The Statesmen, a respected Anglo Indian newspaper, exploited the loophole in censorship which was over the word and not photographs, and published pictures of starving people on the roads of Calcutta. The USA, Britain’s ally in an ongoing World War, sharply criticised the government for making a muck of the crisis.

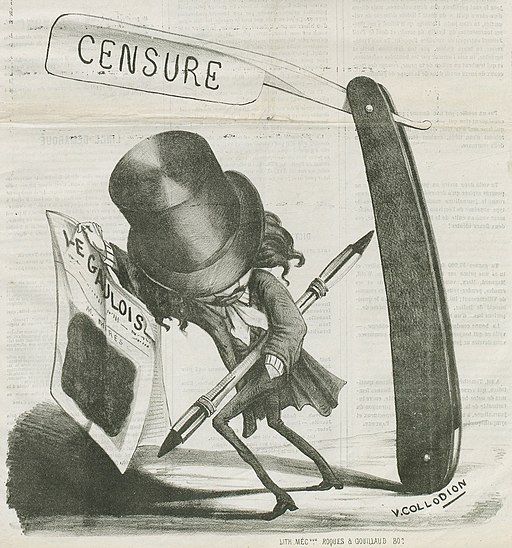

Censure (Le Gauloi)

The Press Act of 1910, 1930, Press Emergency Powers of 1931, and Defence Act of India were no different from the previous suppressing Acts. In spite of this, every overbearing action by the Government proved to be an impetus to the editorial renaissance. Grievances related to taxes, sale of liquor, road cess, disparities in salaries of officials, all found its stentorian voice in daily publication. Going against the dictates of government censorship, prominent editors like Surendranath Banerjee, Arbinda Ghosh, B.G. Tilak, and M.K Gandhi brought politics to the forefront and became the guiding spirits of freedom.

Like in the past, Press is yet again a victim of severe suppression from the government. Constructive criticism becomes a hard pill to swallow when it constitutes an inconvenient truth to reckon with. However, defending criticism is a necessary part of governance and while many do it with courtliness, a few resort to censorship which is typical of an authoritarian government. By throwing iron curtains over their cluttering policies and actions, such governments indirectly acknowledge its guilt. Even the Imperial court, back in 1823, expressed a similar opinion when it said-

“A free press is a fit associate and necessary appendage of a representative constitution. Whenever a government emanates from the people and is responsible to them, the people must necessarily have the privilege of discussing the measures of the Government.”

Sordidly, it continued explaining that, “in no sense of the term can the ‘government of India’ be called free.” Thus closing a pre-colonial argument for a free Press then and there.

An imperial sentiment for its colony cannot be better understood than this. But when a democratically elected government silences the Press, it indicates a change in the nature of its governance. In such cases, the fate of the Press is bound with the fate of democracy.